Tag: funding

The AAB opportunity: which courses and institutions stand to benefit? #hewhitepaper

Trial by fire for VCs? a response to http://bit.ly/j8MUo0 ( @timeshighered )

A manager who has come here with the power of the Privy Council by representing Senior Management.

A man who would come here without experience.

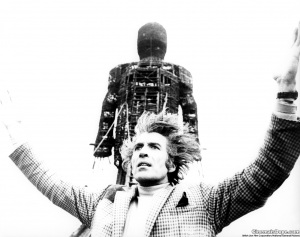

A man who has come here as a fool. VC: Get out of my way. R: You are the fool, Vice-Chancellor – Punch, one of the great fool-victims of history, for you have accepted the role of king for a day, and who but a fool would do that. But you will be revered and anointed as a king. You will undergo death and rebirth – resurrection, if you like. The rebirth, sadly, will not be yours, but that of our Faculty of Humanities. VC: I am a UUK member, and as a UUK member, I hope for the wisdom of the market. And even if you kill me now, it is I who will have been of value to society, not your damned Philosophy course. No matter what you do, you can’t change the fact that I believe in the market eternal, as promised to us by our Lord Browne. R: That is good. For believing what you do, we confer upon you a rare gift these days – a market consolidation. You will not only have experience the market eternal, but you will sit with the bankers among the reviled. Come. It is time to keep your appointment with The Wicker Man. VC: (very agitated) Now, wait! Now, all of you, just wait and listen to me. And you can wrap it up any way you like. You are about to commit murder. Can you not see? There is no public good. There is no education for it’s own sake. Your recruitment failed because your marketing failed. Humanities is not meant to be taught in this institution. It’s against market forces. Don’t you see that killing me is not going to bring back your Faculty? Registrar, you know it won’t. Go on, man. Tell them. Tell them it won’t. R: I know it will. VC: Well, don’t you understand that if your recruitment fails this year, next year you’re going to have to have another blood sacrifice? And next year, no one less than the Registrar himself will do. If the crops fail, Registrar, next year the University Congregation will kill you on Graduation Day. R: They will not fail. The sacrifice will be accepted.

AAB or AARGH? A schoolboy funding error in the #HEWhitePaper

Paragraph 4.19:

“We propose to allow unrestrained recruitment of high achieving students, scoring the equivalent of AAB or above at A-Level. Core allocations [I assume this means allocated student numbers] for all institutions will be adjusted to remove these students. Institutions will then be free to recruit as many of these students as wish to come. Under the new funding arrangements, institutions may be eligible for HEFCE teaching grant for these students, for example those on high-cost courses, and the students will be able to access loans and grants. This should allow greater competition for places on the more selective courses and create the opportunity for more students to go to their first choice institution if that university wishes to take them. We estimate this will cover around 65,000 students in 2012/13.”

The key point here is if a University decides to recruit 50 extra AAB students to, say, a Pharmacy course this means HEFCE has to provide additional funding (you know, the one that used to be called “core funding”) for those 50 students. Don't believe that “may” nonsense, this is a requirement of the model, based around the assumption that lab and clinical sciences cost more to deliver and are of value to the nation. This grant availability could significantly affect the levels of funding that HEFCE would need to make available.

Imagine 50 extra medical students instead, and the exposure of HEFCE (and the NHS) rises further [EDIT: @amacgettigan and others have pointed me to footnote 49 which covers the limiting of medical student numbers] . Basically the extra AAB students only make sense in terms of government funding exposure for non-core funded subjects, not healthcare or lab stuff.