Open Education, and indeed Education Technology more generally, exists in a perpetual “now” – or to be more precise, a perpetual near future. No matter how many times we attempt to put it into a narrative, it retains a deliberate ahistoricity that – after a while – begins to jar. Even to say that we have heard all this before has become a cliché, as there always seems to be one of those sessions at every conference.

It’s usually my session.

“Retain” is the first of Wiley’s “5Rs”. To give the complete language:

“The right to make, own and control copies of the content, eg download, duplicate, store and manage.”

In this formulation it implicitly refers to the virality of open content. Open content doesn’t have to exist in just one place, it can exist simultaneously in multiple (accessible and non-accessible) places. The comparison is with content licensed under a closed licence – it can’t be everywhere you want it to be. Even though Apple Music (say) will temporarily store music on your computer, you can never be said to “own” a copy. And most widely used software (such as windows) is only licensed, never owned. Even the software in your car or tractor is only licensed to you – you can never truly be said to own your car.

Ownership implies a relationship between you, an object, and time. Something belongs to you until you decide not to own it. In the perpetual near-future of “edtech”, ownership is a concept that is almost obsolete.

What about a community? Can you “own” membership in a community? I would argue that you could – membership of the community of open educators is ours as long as we choose to claim it. No one – not even Stephen Downes – can refuse to let you be a part of this community.

But is the community active in time?

Maybe I need to unpack this a little. My first OpenEd was here in Vancouver in 2012 (I was meant to go to Barcelona in 2010 but I couldn’t for various personal reasons). But what did I miss by not being there in earlier years? – what did other attendees bring to the conference in 2012 that I did not? How could I even find out what happened at say, OpenEd2010? Or OpenEd2008? or any of the predecessor conferences?

This is important, because a community of practice is a shared history of that practice. When we all complained about Sebastian Thrun “inventing” open education in 2011 – this was an expression of the history of our practice. Some of us were able to talk about, say, David Wiley’s experiences with WikiClasses in 2005, or George Siemens’ experiments in 2008 and say – look, this is the same thing. We’ve done this, we learnt from it, we want to share what we learned.

But – and I mean here no criticism of a decade of hard-working conference organisers – we are actually quite bad at preserving what we have learned and in particular we are bad at capturing what happened at these conferences.

Open Education is a field often criticised – for being without a research base, for being unconcerned with context and pedagogy, for being blind to the problems inherent to the idea of reuse, for being focused on content rather than community. These are major challenges to the integrity and nature of this field: and we have no real way to answer them.

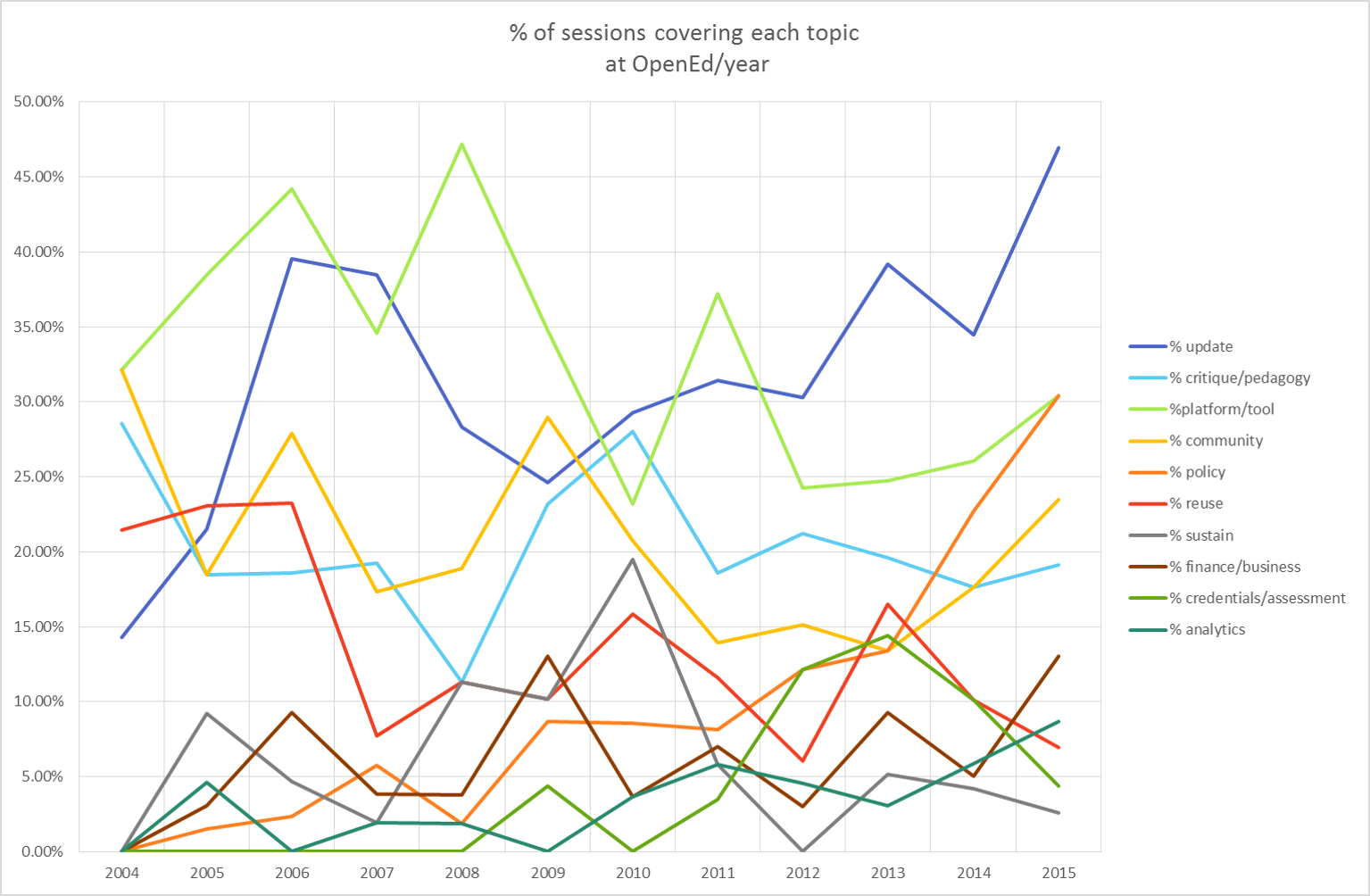

I collected and tabulated 11 years of OpenEd conference activity. Not much, just session titles and presenter names. This took me more than a week, and necessitated me promising not one but two pints of beer to Alan Levine. In some cases abstracts and/or slides were available, in other cases not. I drew primarily on the (amazing) Internet Archive, which captures the old conference sites in various states, allowing for the vagaries of the technology underpinning them. (ColdFusion? seriously…)

I did this to scratch an itch, to see something that no-one else had seen (a similar motivation, I think, drove Adam Croom to serendipitously do a similar job in a slicker way). Others may need to find old abstracts for other reasons. Validation, for instance: to prove that they where at OpenEdxx and they presented on whatever it was. Or research: they’d seen a reference to a great presentation in previous years and wanted to read about it for themselves so they could build more research on top of it.

Some presentations here become papers (or blog posts). Some begin as papers or blog posts. But many more exist as a moment in time, maybe a set of those fashionable slides with big images and not much text. And a presentation that held the room. Maybe every presentation is captured as a youtube video, or an audio file – some years it is, some years it isn’t.

And as you can see, there are patterns in there. I talked about the peaks in critique and sustainability talk in 2010 (linked to the end of many Hewlett grants at that time), the slow but inexorable growth of “policy” as a theme, and the dearth of interest in “reuse” since ’06. The tags are broad and subjective – in releasing the data I’m hoping people will feel bold in using their own tags to drive their own understanding. (The only unclear tag I use was “update” – just a way of indicating sessions primarily focused on providing an update on an ongoing project. I was heartened and surprised to see more updates this year than ever before – clearly there are more projects running than people may realise)

But the real focus of the session was just to help the community get better at archiving findings and building on them. If open education ever grows beyond simple implementation, this is how it will happen.

13 thoughts on ““Keep the Fire” – notes on my #OpenEd15 presentation”