David Kernohan – presentation at ALT-C2013, Nottingham. This is the complete text of the presentation, with added links for clarity

As long as there has been education, it has been broken. For all the struggles of the finest teachers, for all the ingenuity of the greatest publishers, for all the grand buildings, the government regulations, the league tables and swathes of measurement and data – sometimes some people did not learn something that it was expected that they would.

This is not their story.

It is, in fact, the story of an entirely different group of people, many of whom have seen some significant success in their own education, others of which gave up on the whole thing as a bad job and have been grumpily poking it with sticks ever since. These are the people who go around reassuring us that – not only is education broken, but it is clear that somebody should do something.

In this group I would include several commentators, salespeople, bloggers, Sir Michael Barbers… but most of all I would include journalists.

Education, and the use of technology in education, has not historically been a subject to set printers rolling (except possibly in a purely literal sense with Gutenberg in 1439). There was a brief period at the turn of the century… words such as UK eUniversity and Fathom.com spring, unbidden, to mind; and a short blip back in 2010 when everyone got so impressed with their iPad that they assumed it would replace just about every living and non-living entity in the observable universe. But still, it was an “interesting aside on page 4” thing, not a “hold the front page” thing. Sandwiched between a gratuitous picture of a semi-famous woman with dead eyes in a revealing dress and 8 densely packed paragraphs of political speculation read by no-one and believed by fewer.

And then, in 2011, the world changed. George Siemens drew the link between experiments in online Connectivism mainly conducted in Canada, and a bold initiative from Stanford University to share advanced courses in Robotics. Of course, that initiative became what we know as Udacity, and built upon a great deal of now largely forgotten work at Stanford by John Mitchell, developer of their in-house CourseWare platform, and decades of earlier research and development across the world.

Do you remember where you were when you read your first MOOC article in a proper newspaper? For most I imagine it was when the comment section of the New York Times threw a spectacular double punch in May 2012 – firstly David Brookes’ “Campus Tsunami”, followed a week later by Thomas Friedman’s “Come The Revolution”. These articles were sparked by the launch of an unprecedented third MOOC platform, MIT and Harvard’s EdX, alongside Udacity and Coursera which both spun out of Stanford.

These two early articles are in many ways emblematic of the way in which the MOOC has been presented. Monster-movie titles. A focus on millionaire rock-star entrepreneurs, who just happen to have done a bit of teaching and research. And each of these articles mentions the word “open” only once, the first in the context of the “wide-open” web, the second in the context of opening up opportunities to gain qualifications.

Interestingly, neither mention the word “MOOC”.

I examined the first substantial main-paper MOOC-related article (not comment, where possible) from a range of mainstream sources on the web. Reuters. The Washington Post. The Daily Telegraph. The Guardian. (interestingly the Daily Mail has yet to tackle the topic – do MOOCs cure or cause cancer? The ongoing obdurate online oncological ontology awaits urgent clarification).

| publication | date | title |

| New York Times |

02/11/2012 |

The Year of the MOOC |

| The Atlantic |

11/05/2012 |

The Big Idea That Can Revolutionise Higher Education: ‘MOOC’ |

| The Guardian |

11/11/2012 |

Do online courses spell the end for the traditional university? |

| Financial Times |

22/10/2012 |

Free, high-quality and with mass appeal |

| Washington Post |

03/11/2012 |

Elite education for the masses |

| BBC News |

20/06/2012 |

Top US universities put their reputation online |

| The Telegraph |

03/08/2012 |

Distance Learning: The Online Learning Revolution |

| Time |

18/10/2012 |

College is dead, long live college |

| Huffington Post |

05/08/2012 |

MOOCs From Elite Colleges Transform Online Higher Education |

| Fox News |

27/12/2012 |

Will college be free someday? |

| Reuters |

19/10/2012 |

Getting the most out of an online education |

I used text mining tools to visualise commonly linked concepts in these articles. Text mining is a complex and multifaceted methodology, and I don’t claim to understand it all. I simply plotted closely related words using a “communities” focused modularity, seeking words that frequently correspond. But just think of this as a slightly fancier wordle.

Again, one searches in vain for the word “open”. The larger, purple blobs are the most common – they focus on the nub of the story, as perceived by multiple journalists. Students, courses, online higher education offers. You can also see a turquoise community of terms dealing with (for anyone with press training) what looks like your paragraph 3 background stuff, names, locations. Sebastian Thrun (famed for not inventing Google Glass, driverless cars, StreetView and online learning) looms large. And the yellow blobs seem to describe the student experience… a free online class with videos, where you can get a certificate to show employers.

In 2010, Henry Giroux was lamenting the dumbing down of education in the review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies. In a long and densely argued article of parallels and sympathetic resonances between austerity in education and the Greek resistance to what he describes as neo-liberalism (before George Siemens decided we couldn’t do that any more), the following lines really stood out for me:

“while a number of other institutions are now challenging the market driven values that have shaped [western] society for the last thirty years, education seems to be one of the few spheres left that is willing to enshrine such values and, with no irony intended, does so in the name of reform.”

Richard Hall extends a similar argument to the sphere of technology in education:

“This increasingly competitive, efficiency-driven discourse focuses all activity on entrepreneurial activity with risk transferred from the State to the institution and the individual. The technology debate inside higher education, including MOOCs, falls within this paradigm and acts as a disciplinary brake on universities […]. What is witnessed is increasingly a denial of socialised activity beyond that which is enclosed and commodified, be it the University’s attempt to escape its predefined role as competing capital, or the individual’s role as competing, indentured entrepreneur.”

Or Lesly Barry, of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette said just last week:

“Many of us know the situation first-hand. Universities nationwide are being forced to curtail programs. Students graduate with a debt burden that severely limits their horizons. Many faculty are part-timers without access to a living wage, let alone resources for teaching or professional development. Libraries have had acquisitions budgets eliminated, and journal subscriptions cut. Faculty and students are no longer considered primary stakeholders in the university, and administrators are tasked with repurposing our institutions to more commercial ends.”

These values are enshrined not, in fact, by the actors in the education system but by observers of it – namely politicians, policy-makers and journalists. And, the increasingly techno-deterministic educational discourse, bringing with it a focus on quantitative measures and whispers of “artificial intelligence (in reality, a simple set of algorithms and a great paint job) means that increasingly the first two groups are relying on a summary provided by the third.

This is why the quality of education technology journalism is one of our bigger problems, and why I expend such a lot of energy writing and talking about it.

One of a very small numbers of generally great Education Technology journalists, Audrey Watters describes the problem:

“Indeed, much of the hullaballoo about MOOCs this year has very little to do with the individual learner and more to do with the future of the university, which according to the doomsayers “will not survive the next 10 to 15 years unless they radically overhaul their current business models”. […]“Will MOOCs spell the end of higher education?” more than one headline has asked this year (sometimes with great glee, other times with great trepidation). As UVA’s Siva Vaidhyanathan recently noted, “This may or may not be the dawn of a new technological age for higher education. But it is certainly the dawn of a new era of unfounded hyperbole.” The year of the MOOC indeed.”

I’ve had the experience of speaking to a huge variety of journalists about MOOCs – I’m the chap you phone up if Martin Bean’s phone is engaged and Martin Weller isn’t answering email (I’ve no illusions). Each time I’ve patiently and carefully taken journalists through the history, the nuance of the term, the pedagogic underpinning, what we already know about learning online and learning at scale. Each time they’ve gone away and written the article they want to, full of hype and natural disaster metaphors.

But maybe that’s just how to get page impressions. At least real decision makers get better advice than this.

It would be unfair to discuss the problem of MOOC hyperbole without a glancing mention of “Avalanche Is Coming”. Sir Michael Barber – a very interesting gentleman whom time pressures forbid me to examine in more detail at this juncture – was the lead writer behind IPPR’s much derided report into the “disruption of higher education”. Sir Michael is not a journalist – he has a background in education and government, so has absolutely no excuse for feeding this beast.

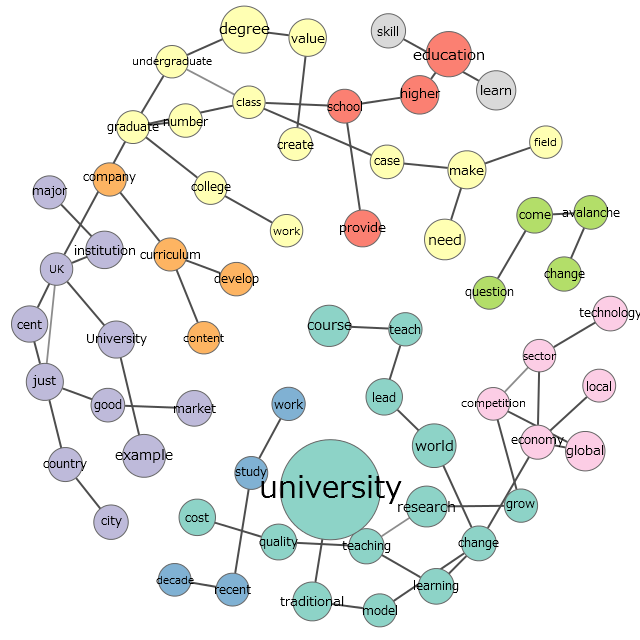

In a similar way to my corpus of MOOC articles, I’ve also produced a plot of commonly linked concepts in “Avalanche”:

The repeated co-incidence of company, curriculum, develop and content was a particular delight (orange blobs). And open is nowhere to be found.

But, looking at the fine detail both of the co-incidence plot and the report itself we are looking at a superb example of the links between the MOOC hysteria and the commercial and instrumentalist unbundling project. The repeated emphasis on study leading to work, a need for change in order to facilitate competition and the internal dismantling and “de-organisation” that Deleuze and Guattari talk about before they get to the rhizomes in “A Thousand Plateaus”.

“Open” was the first organ that we lost. From a nuanced and specific position in the world of the open educational resource, it is a word reduced to a synonym for two senses of free – free of cost (free as in beer) and free of prerequisites (free as in ride). Freedom, of course, is another word for nothing left to lose – yet somehow we have managed to lose it anyway.

Mike Caulfield puts the birth of the basis of conceptual machine learning at 1954 with Skinner – but novelty and the notion of a response to changes in society is another key trope. We’ve decades of high quality research in the field of learning facilitated by machines, yet to the op-ed crowd MOOCs are the latest thing.

We are really still in search of Newman’s “intellectual daguerreotype”.

“The general principles of any study you may learn by books at home; but the detail, the colour, the tone, the air, the life which makes it live in us, you must catch all these from those in whom it lives already. You must imitate the student in French or German, who is not content with his grammar, but goes to Paris or Dresden: you must take example from the young artist, who aspires to visit the great Masters in Florence and in Rome. Till we have discovered some intellectual daguerreotype, which takes off the course of thought, and the form, lineaments, and features of truth, as completely and minutely as the optical instrument reproduces the sensible object, we must come to the teachers of wisdom to learn wisdom, we must repair to the fountain, and drink there. Portions of it may go from thence to the ends of the earth by means of books; but the fullness is in one place alone. It is in such assemblages and congregations of intellect that books themselves, the masterpieces of human genius, are written, or at least originated.”

And our press have mistaken a restatement of this possibility for the thing itself. Our position, as educators and as researchers in this field is to be honest, even to the point of negativity. David Wiley’s Reusability Paradox has not yet been solved, participation and engagement in online communities is still an exception rather than a rule, resources adapt to learners rather than the other way round, and fully online learning remains a niche. There is still so much work to be done.

Giroux, as cited above, talks of:

“a concerted ideological and political effort by corporate backed lobbyists, politicians, and conservatives to weaken the power of existing and prospective teachers who challenge the mix of economic Darwinism and right-wing conservatism now aimed at dismantling any vestige of critical education in the name of educational reform.”

As peculiar as it may now, seem, the open education movement began in opposition to this effort. Those of you who engaged with things like the SCORE project and the UKOER programme will remember the conversations with incredulous academics and managers. The range of benefits, exemplars, business models and rationales that we can all now rattle off – and the majority of these now have considerable evidence behind them, were far less clear in 2008 and 2009. The fear of “giving away the crown jewels” to the benefit of the world has been replaced by a huge eagerness to give away these same gemstones to private companies spun out of Stanford and the OU.

(and don’t think that it is because of OER not being aimed at students – Audrey Watters wrote only last week about a swathe of commercial lesson plan sites and courseware directories being the unexpected commercial edtech theme of the year)

As Brian Lamb and Jim Groom asked: “Has the wave of the open web crested, its promise of freedom crashed on the rocks of the proprietary web? Can open education and the corporate interests that control mainstream Web 2.0 co-exist?”

To look again to the way the New York Times reported the initial OCW idea, this time with Carey Goldberg “Auditing Courses at M.I.T., on the web and free”.

“Still, is the institute worried that M.I.T. students will balk at paying about $26,000 a year in tuition when they can get all their materials online?

”Absolutely not,” Dr. Vest [then M.I.T. President] said. ”Our central value is people and the human experience of faculty working with students in classrooms and laboratories, and students learning from each other, and the kind of intensive environment we create in our residential university.”

”I don’t think we are giving away the direct value, by any means, that we give to students,” he said. ”But I think we will help other institutions around the world.””

Looking across a range of OER/OCW articles from the mid-00s onwards (using the same methodological approach as the MOOC articles above) I came up with the following corpus:

| New York Times |

01/11/2010 |

For Exposure, Universities Put Courses on the Web |

| The Atlantic | x | x |

| The Guardian |

17/01/2007 |

The Great Giveaway |

| Financial Times |

21/04/2008 |

Adult Workers have a lot to learn online |

| Washington Post |

31/12/2007 |

Internet Access Is Only Prerequisite For More and More College Classes |

| BBC News |

23/10/2006 |

OU offers free learning materials |

| The Telegraph |

25/11/2010 |

Why free online lectures will destroy universities – unless they get their act together fast |

| Time |

27/04/2009 |

Logging on to the Ivy League [UNABLE TO ACCESS FULL TEXT] |

| Huffington Post |

10/08/2009 |

Narrowing the digital divide |

| Fox News |

29/12/2007 |

Internet opens elite colleges to all |

| Reuters | x | x |

| Times Higher Education |

24/09/2009 |

Get it out in the open |

And using the same plotting technique as above:

There was no talk here of “disrupting” education – if anyone was being disrupted it was the publishers who take the work of academics and sell it back to them. The concept of a “direct value” in on campus education now seems impossibly quaint – MOOC talk attempts to short circuit this by an elision of value and recognition in the offer of certification. These certificates, and the faltering attempts to link them to university credit, have entered what I’ve decided to call a Baudrillardian hyperreality of education, no longer signifying anything but the perceived importance of the processes that generate them.

Of course, the process (rather than the practice) of education is what drives the MOOC world. Writers without a critical perspective on both education and technology can be lulled into a simple skeumorphic model of replicated offline models re-established online. You can see large classes witnessing lectures by “rock star professors”, simple quizzes to reflect understanding, discussion groups, assignments and required reading. The process ensures that all of this is measured, monitored and recorded – both (somehow) to accurately gauge student achievement and to refine the process.

Hand and Sandywell, in “E-topia as Cosmopolis or Citadel”, suggest that:

“Adorno’s conception of the administered society and Foucault’s panopticon have been given digital wings, where societal regulation is seen as operating through the capillaries of information exchange. We shift from industrial to post-industrial forms of regulation. Where the original panopticon secured compliant bodies for the industrial process, the cybernetic panopticon of digital capitalism produces docile minds locked into their screens”

Foucault’s original point regarding Bentham’s Panopticon (in “Discipline and Punish”) was that it was the possibility of observation rather than the actuality of observation in such a situation that brought about obedience – “to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power”. The process, however, induces in the MOOC inmate a consciousness of observation as a component of a totality – she knows that there is no chance that the superstar academic is watching her as an individual as the academic is not there, but she is painfully aware that the platform is watching her every move for its own, manifestly non-educational, purposes.

So, then, as anyone that has participated in an xMOOC will know, the game playing begins and the peer assessment becomes a lottery of either unsubstantiated criticism or a timid “that was great”. The process is complete, the value is… well, that’s not for me to say.

The thrust of “E-Topia” concerns the need for a refined theoretical language to properly situate the effect of internet technologies on the global socio-political discourse. And I would, of course, support such an aim. But I would argue that the construction of a language that can convey the realities of education, be it on- or off- line, massive or personal, open or “open” – away from the crumbling narrative of the market, is the essential first step. To close with more words from Audrey Watters:

“We need to get better at asking who is telling these stories. We need to ask why. We need to think about how we plan to tell our stories – our narratives and our counter-narratives. How do we make them “stick”?”

At the very least, we need to begin telling those stories. We need the confidence, almost the arrogance to stand up with nothing more substantial than a compelling story. Because that’s what every MOOC start-up under the sun is doing that, to journalistic applause and repetition, and it seems to be working very well for them.

I pretty much agree with the sentiments behind your post David, but it occurs to me that you are analysing US Universities, who are obeying Clayton Christensen’s dictum on disruptive innovation, using French theorists who delighted in building ‘machines for thinking in’ as I call them.

I, and the colleagues I work with, try to address problems in British education developing local ideas. For example the Open Context Model of Learning which started from the point that OER’s are not enough so develop a model of learning appropriate for that, and evolved the Pedagogy, Andragogy, Heutagogy (PAH Continuum). Pedagogy is not enough in an open world (not least as it is implicitly a hierarchical model of learning). of course this was developed with Ronan O’Beirne, Rose Luckin, Nigel Ecclesfield, Wilma Clark, Judy Robertson, Peter Day, Drew Whitworth amongst others.

We further developed the Emergent Learning Model based on what we had learnt from how technology affects learning. From this we have developed both the andragogic Ambient Learning City and the heutagogic WikiQuals. neither of which have raised a flicker of interest from JISC (who funded the first) or ALT-C ‘community”. Not only are we Brits technophobic we are also Francophiles and in awe of the American Empire. We dont have to wring our hands, we can transform education and we can do it at home. #altc2013 http://www.slideshare.net/fredgarnett/wikiquals-pecha-kucha

I spend so much time putting out spot fires because of this constant MOOC bollocks. I’m no Ludite, I’ve been evangelizing the thoughtful integration of technology into day to day teaching for the past 15 years. I’m trying to harness the hype and redirect the conversation, but the utter ‘back to the future’ nonsense that keeps coming out makes that difficult.

I drew a comment from my boss for putting this in the department’s public eLearning blog.

‘Apart from Audrey Watters, can anyone point me in the direction of proper journalist reporting on MOOCs who isn’t a total moron or commenting on a field they only marginally understand.’

He agreed with the sentiment but thought moron was a little strong. After I explained that my original text was ‘total F’ wit who couldn’t find his arse with both hands’ he agreed I had shown remarkable restraint (but still told me tone it down a little).

(And while I’m at it, Khan isn’t an Academy, it’s a digital resource repository).

An interesting analysis of the impact, or not, of MOOcs on HE institutions and teaching & learning in general. While I agree with a lot of what David says, he does forget that one reason for education being broken is that it continues to follow the one-size-fits-all model. So, rather than criticising xMOOCs and their rock star professors, he should remember that not everyone has had his educational opportunities, and that for them, participating in an xMOOC could a great and worthwhile learning experience. It’s easy to criticise the MOOC frenzy but, at the end of the day, if we are going to fix education the status quo needs to be disrupted and new models need to emerge from the chaos.

I think this is important to point out Will. I have a close friend who has no formal education beyond school (and left school with a handful of qualifications). She is in her forties and is in the middle of her first formal educational experience since the age of 15. It happens to be an xMOOC through Coursera which she values as a “worthwhile educational experience” because it is free, she can fit it around her part-time work commitments and she can watch the videos, answer the quizzes and contribute to the discussion on her iPad while sitting on the couch. She doesn’t give a shit about whether the professors are ‘rock stars’ or not.

xMOOCs are far from perfect, and I don’t buy into the MOOC frenzy either. But there seems to be an increasing tendency among those who have had relatively privileged educational opportunities to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

I agree with you both – no-one should be implacably against anything that helps people learn, xMOOCs included.

What I am against (as in the post) is the tenor and tone of the surrounding hype, which is blinding us to ways we could use the web more effectively to support learning – building on years of research and evidence that appears to have been ignored.